Music is ubiquitous today – you can’t even go to the grocery store without listening to ambient tracks as you look through the aisles for dinner ingredients. Although music seems to be everywhere, it wasn’t always as easy as pressing play on Spotify.

Indeed, the changes in how we’ve listened to music over the past few decades are considerable. These shifts have altered the business model for musicians and our social conceptions of music listening. It started with improvements in physical technology: from vinyl to cassette to CDs – each iteration becoming more compact, portable, and user-friendly than the last. With each of these inventions, more and more people were able to access music and listen to it at a higher rate. The move from vinyl to the invention of the Walkman, for instance, meant that we could now take some our music with us wherever we went. Consumption has steadily been on the rise, with music becoming a bigger aspect of our lives with each shift.

So let’s break this down further. Before anyone was able to record music, the only way to hear it was live. This meant traveling down to the local theater to watch the performer sing in person. Without any way to copy the music short of learning and performing it yourself, the law was straightforward as laws can be: it didn’t exist because the thing it was protecting didn’t exist yet.

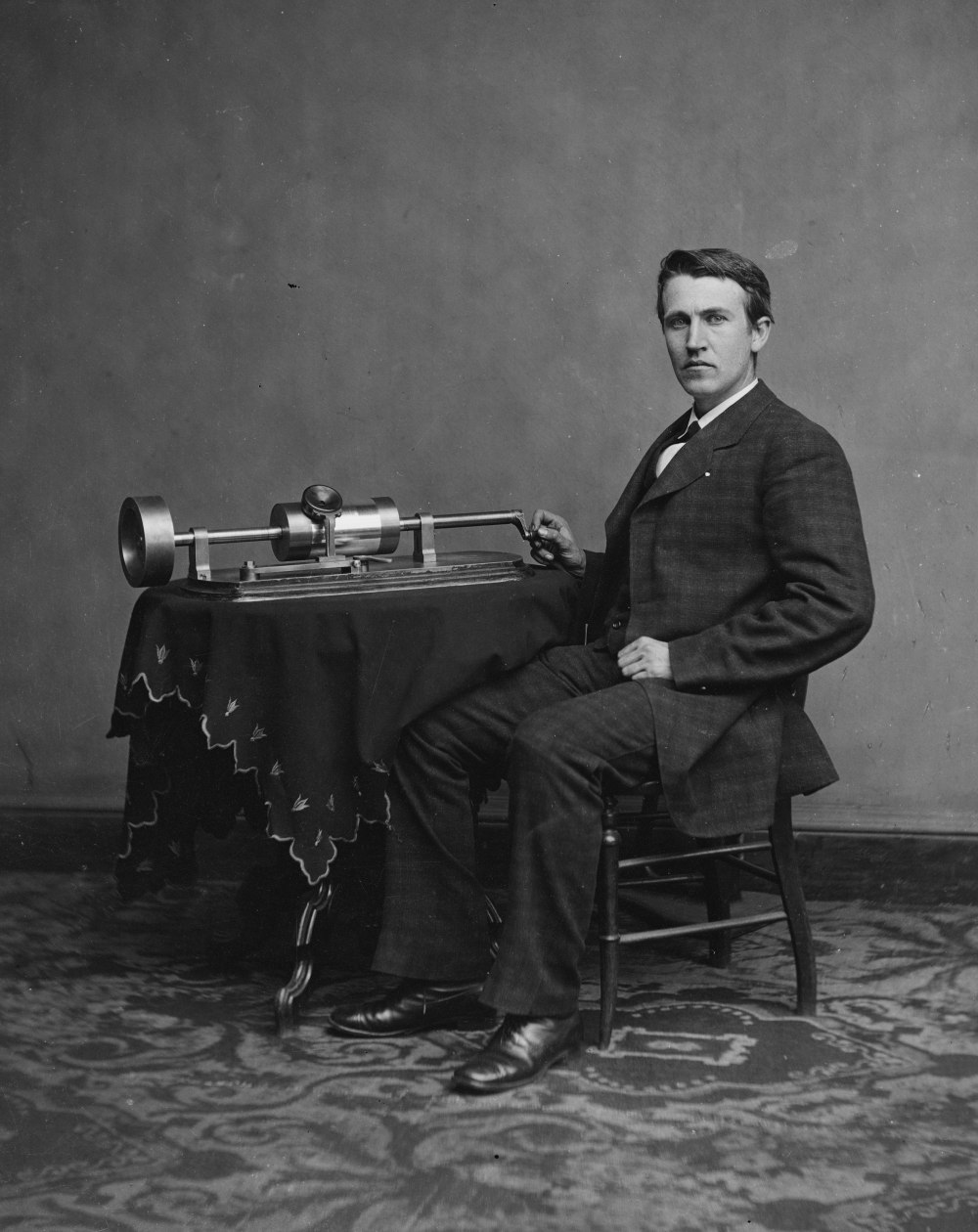

Then in 1877, Thomas Edison invented the Phonograph. This revolutionary piece of technology meant that consuming music was no longer limited to experiencing it live and in person. Music and performances could now be distilled into a physical representation and the sound could be reproduced exactly how it was recorded. This opened the door for many business opportunities, but for the music industry, this meant listeners of music could enjoy performances in a completely different time and place. This invention opened up the door for many new technological and commercial innovations.2

In the 1890s this technology was used to create the jukeboxes. Seeing the business opportunity, companies created a coin-operated machine that could play these recordings. These machines found homes in social venues as entertainment. For those venues, it was a way to attract keep customers coming. But for the music industry, it became a way for music to spread. Musicians had a medium to get more attention, for their works to propagate through cities farther than could travel.3 And as the technology of the Phonograph progressed, like with the rise of the Victrola, so did the efficiencies and mechanisms of the Jukeboxes, increasing their potential to spread culture.4

However, this innovation didn’t conform to the law well. The Copyright Law was passed in 1909, and coin-operated music machines were not considered public performances. Intellectual property law is designed to protect the owners and creators of the music. For music writers and producers, this meant that they had the rights to their own produced content and had the right to license or charge others for using it. But, the law lags behind technology. In 1908 the White-Smith Music Publishing Co. v. Apollo Co. Supreme Court case, the Supreme Court ruled that because player piano rolls were printed in a format that was to be interpreted by a machine, it was not considered a copy of the music.5 Therefore, music that is not read by the human eye is not considered a copy, and the music writer could not claim royalties for the playing of the music by player pianos. This set the precedent that if the music is not in a human readable format or is not considered a public performance, the owner of the music could not make a profit off of it.6 This was not amended until 1971.

So even though music was being widely distributed through jukeboxes, the owners and renters of these products were making money and the listeners were able to enjoy the music, but the writers and owners of the music got no benefit. The recordings were bought once, but were redistributed to earn a profit. The innovation in technology revolutionized how music was consumed and spread, but the misunderstanding of how this technology worked took power away from music producers.

Between 1930 and mid 1950, radio gained traction as a new form of entertainment. In addition to talk shows and news, music was broadcasted over the air. One of the innovations to come about from the radio was the concept of the Top 40 station, which arose from seeing jukebox users play the same songs over and over again. At this time, radio receivers and broadcasters were largely AM. In 1933, FM radio was patented by Edwin Armstrong and offered higher quality sound, was initially slow to gain traction. The affluent pioneers of the FM radio stations held largely different tastes than consumers of AM radio stations. So when FM radio started taking of in the 1960s, classical and jazz was largely played, but new music and ideas were tolerated.7

However, during this time, the power for compensation was still largely out of the hands of musicians. Radio stations rarely paid royalties, and many major record label companies fought to try and secure payment for the content used. On the other hand, smaller record labels often gave the radios permission to play their music for free, using the platform as promotion of their content.8 It was clear that it would be difficult to ensure that music ownership and compensation would be respected.

In the 1940s, a new vinyl format began to take to the market, able to hold more and better quality music. Vinyl was the medium of choice, especially as jukeboxes evolved to use these and as phonographs became more affordable and were more common in homes.9

In 1963, the compact cassette tape was introduced, but didn’t really become popular until the 1980s because of the low-quality sound initially. But eventually, sales of the cassette tape surpassed that of vinyl thanks to the convenience and portability. These cassette tapes could be played in cars, boomboxes, and even personal Walkmans. In addition, its format made it simple to copy music onto it for personal enjoyment,. However, this led to the problem of sharing music, once again, undermining the potential profits earned by music artists.10 This was especially important because in 1971, Congress passed the Sound Recording Act, which meant copyright protection now extends to sound recordings.11 This means that the owners of the music on sound recordings, whether they are the musicians or the record label companies, have copyright protection for the sound recordings. However, this didn’t stop consumers from copying and sharing music.

In 1982, the compact disc was introduced. It revolutionized the storage of audio by allowing music to be encoded in a digital format. This meant that it could sound good with any digital player, unlike previous analog formats, on which the quality of the sound was dependent on the state of the record or cassette tape. With time normal wear and tear would degrade the quality of music.12 The affordability and better performance of the CD quickly made it the format of choice. In 1988, CD sales exceeded that of vinyl, and by 1991, CDs overtook cassette tapes.13

Electronics companies also were improving their products to support the CDs and provide better sound quality. Sony developed the Rotary head Digital Audio Tape, or DAT, which allowed consumers to record audio in a digital format. The music industry was concerned that this new technology would make music perfectly cloneable, so it pressured the government into halting the commercial development of DAT recorders. Home taping was a legitimate fear, because it meant that any consumer could reproduce music an unrestricted number of times. This would compete with sales of pre-recorded music. The problem of unauthorized duplication led to the music industry lobbying Congress to pass legislation. In 1992, the Audio Home Recording Act was passed, which mandated manufactures of digital audio recording devices must have some sort of mechanism to prevent the unrestricted copying of audio. The solution for this was the Serial Copy Management System (SCMS) built into every DAT recorder. This solution restricted the number of copies that could be made from a source to one. This was designed to protect music distribution corporations from the opportunities technology brought about. However, DAT recorder use was limited to semi-professional music recorders, and did not become mainstream consumer items.14

On the other hand, innovation in CDs once again brought up the issue of copyright. The introduction of the CD-R (recordable CD) meant that consumers could copy the digital encoding of the music and make copies with no degradation of quality. There was no SCMS for CDs and computer equipment didn’t fall under the Audio Home Recording Act. In fact, because Information Technology Industry Council was concerned that putting similar restrictions would fundamentally inhibit innovation of computers, the Audio Home Recording Act includes a clause that excludes audio files on computer hard drives from the definition. But while this provision was good because it didn’t stifle the technological innovations of the computer, it ultimately did little to protect the music industry moving forward.14

In the 1989, the MP3 compression algorithm was developed. This algorithm was a process for taking the digital audio format and reducing the size by compressing the content with an extremely complex process. Depending on the compression rate, a digital audio file could be reduced to 22 times its initial size. This is made possible by removing information or sounds we can’t hear by auditory masking, as well as discarding data that falls below the Minimum Audition threshold. Yet, compressing an audio file to one-eleventh of its original size could produce near-CD quality. However, it wasn’t until 1996 that the microprocessors in computers could decompress the MP3 files in real time for listening.14

The MP3 algorithm made it possible to take large audio files and compress them into a fraction of the original size. Now consumers can keep their music on their computer. But it also meant that music was much easier to copy and share. And because it was not prohibited by the Audio Home Recording Act, there were no systems in place to prevent users from doing so. This made piracy of music more accessible and widespread. Consumers could now take music, compress it into files of manageable size, and share it over the internet and completely bypassing any copyright law. For more on piracy, see Intellectual Property Concerns.

In 1995, RealNetworks pioneered the concept of streaming with the launch of their product RealAudio. Streaming, playing content in real time over the internet, wasn’t a major revolution, considering music was already broadcasted over the radio. However, as we’ve seen, the streaming technology has fundamentally changed the music industry.15

Concept of selling music on the internet began with Capitol Records in September of 1997. The record label company sold well-known artist Duran Duran’s radio edit “Electric Barbarella” for 99 cents. While this innovative change was perceived positively externally, it completely disrupted the music industry. It set a completely new standard that record labels were unprepared to handle.16 But this change created a completely new way for consumers to acquire and listen to music. Instead of having to go to a store to purchase a CD, they could now get the music in a digital format online and burn a CD if they desired.

In 1998, the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DCMA) is passed. This law criminalizes any technology that circumvent measures to prevent copyright infringement, and the production of said technology. But while this made piracy and pirating platforms clearly illegal, it’s difficult to enforce. For more, visit Intellectual Property Concerns.

In 1999, Napster was released. This platform allowed consumers share MP3s from their computers over a distributed network for free. This service completely bypassed any copyright regulations and didn’t compensate the music owners for their work. This platform boomed. In the summer of 2000, about 14 thousand songs were downloaded per minute. Some artists embraced it, realizing that this was free marketing. However, the majority of artists and record labels were upset that their music was being disseminated without their compensation. All structures of payment, like the royalty system, were useless with Napster and other peer-to-peer music distribution systems. Eventually, the Recording Industry Association of America, Metallica, and Dr. Dre sued for copyright infringement. Napster was ordered to either start charging money or shut down. No longer a source for free music, Napster lost its appeal.17

In 2003, the iTunes store entered the scene, again changing the landscape of music sales, listening, and distribution. iTunes not only changed how much music we could access and how frequently we listened to music, but it also shaped the purchasing process. iTunes introduced many new concepts, one of the most influential being the ability to buy single songs. This disruption completely changed the buying and listening behavior of consumers. The norm shifted from purchasing an entire album to picking and choosing which songs you bought – introducing the power of the Hit Single. While not strictly good or bad, this changed artists’ business strategy when creating and marketing music. Consumers used to take an album as-is. Today, with the ability to buy single songs and create playlists of our favorites, music has become more pick-and-choose – pick one song from this artist and another from that and create your own album; in a sense.

Yet, digital downloads might soon be an outdated concept.

We’ve reached the next paradigm shift in the music industry: streaming. Read more about streaming and its implications here.